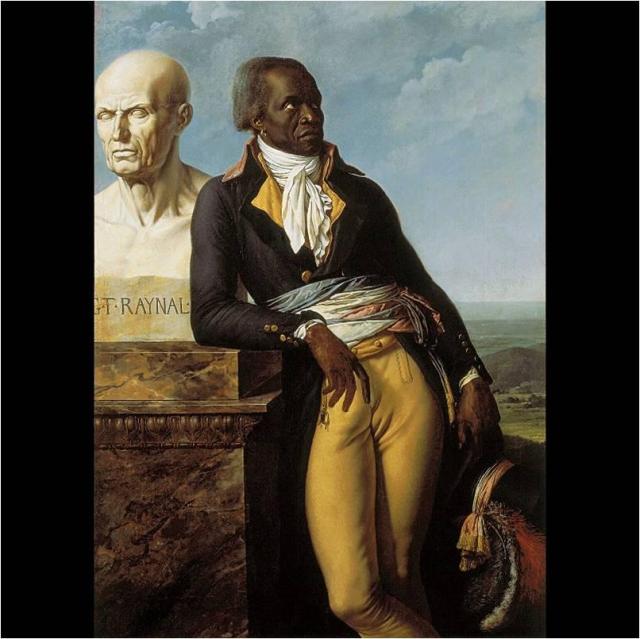

Jean-Baptiste Belley, the elected representative of St. Domingue in the French Revolutionary Convention, 1797. He leans on the statue of the Abbé Raynal, a white advocate of the rights of slaves.

The recent textbook of world history — winner of the 2011 World History Association prize — by Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper, Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference, provides a well-researched, thoroughly-documented, balanced interpretation of the history of humanity without nation-states at the center. Burbank and Cooper’s thesis is that through most of the recorded history of humanity most people lived in empires, right down to the present day.

One reason to pay attention to this presentation is the insight it offers into the history of the, as it were, empire of the United States. For a start, empires have been ever since Rome, rather fantastic in their self-image: the reader may recall Augustus Caesar’s insistence that he was merely a distinguished member of the Senate.

Augustus restored the outward façade of the free Republic, with governmental power vested in the Roman Senate, the executive magistrates, and the legislative assemblies. In reality, however, he retained his autocratic power over the Republic as a military dictator. By law, Augustus held a collection of powers granted to him for life by the Senate, including supreme military command, and those of tribune and censor. It took several years for Augustus to develop the framework within which a formally republican state could be led under his sole rule. He rejected monarchical titles, and instead called himself Princeps Civitatis (“First Citizen of the State”). The resulting constitutional framework became known as the Principate, the first phase of the Roman Empire.

From the point of view of early U.S. history then, the hypocrisy of the first words of the Declaration of Independence appear no worse than that of an emperor of Rome who claims to be no more than the First Citizen. (Note, incidentally, how close that title is to the one Napoleon Bonaparte assumed as he ruled France following a military coup d’état — “First Consul”. In his case he soon dropped the pretense and took the title of Emperor of the French within a decade.)

France was an empire at the time of the French Revolution, and, as Burbank and Cooper explain (pp. 226-228), French planters in St. Domingue [what is now Haiti] demanded a measure of self-rule. That is, they wanted just what the British subjects of the United States had won not a decade before from King George III. However,

[T]he revolutionary assemblies in Paris also heard from gens de couleur, property-owning, slave-owning inhabitants of Caribbean islands, usually born of French fathers and enslaved or ex-slave mothers.

Notice that it was unique to the Southern states of the United States, the conception that the child of a master and a slave was born without the freedom of his father, and was perpetually a slave. These free people of mixed heritage owned one-third of the land of St. Domingue and one-quarter of its slaves.

Citizenship, they insisted, should not be restricted by color. The Paris assemblies temporized.

It was only under the pressure of a slave revolt that the metropolitan authorities gave citizenship to free gens de couleur and then, when that appeared to be insufficient to stop the outbreak of resistance to French authority, liberated all of St. Domingue’s slaves as well, granting all adult male residents citizenship in the French Republic.

The concession worked.

Toussaint L’Ouverture . . . contemplated for a time allying with the Spanish, but when France, not Spain, moved toward abolishing slavery, he went over to the French side, becoming an officer of the republic and by 1797 the de facto ruler of French St. Domingue, fighting against royalists and rival empires and in defense of ex-slaves’ newly claimed liberty.

Five years later Napoleon imprisoned L’Ouverture under offer of safe-conduct and re-instituted slavery. Burbank and Cooper place this sordid episode of imperial rule in context by showing, throughout their 500-page discussion, how various empires employed a variety of tactics, varying with the times, to rule over inhomogeneous populations with differing sorts of methods, professing consistency while practicing discrimination.

The United States of America satisfies the usual criteria of empire, from its very inception. The territory had a variety of ethnic groups, treated its inhabitants with pragmatic brutality, and rested ultimately on force to establish its writ. Just as Rome had its elections, so did — does — the United States. Now, admittedly, the most recent Presidential election, in which the candidate who spent the lesser amount of money won despite the opposition of the entire gamut of leading elites, does indicate a certain remaining degree of democracy in our country. But the actions of the new government betray the futility of even that victory.

Interpreted as the history of an empire, the purported horrific racism of this country is recognizable as the analogue of strategies adopted by other empires, throughout the history of humanity, to establish and maintain central control over distant provinces and populations. The British means of ruling the Irish, for example, involved the granting of a Parliament in 1782 and its revocation in 1801. The French, of course, condemned Perfidious Albion, but the historically informed has to regard the English elites as similar to, if not indistinguishable from, the writers of treaties with the Native American Indians. The arrival of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 echoes the liberation of the slaves of St. Domingue, and the 1877 end of Reconstruction the re-imposition of slavery by the successor to the French Directorate.

From the perspective of the history of the world as a history of empires, George Orwell’s prescient picture of 1984 loses some of its originality; the world has always had a number of competing empires, and the empires have always been run hierarchically, concentrating power at the center as much as possible. We have at present, just as Orwell wrote, the empires of Russia, China, and the United States. The interaction among them, and their relations with the smaller, less powerful states of Europe, Africa, Latin America, and South Asia constitute international politics.

Just as Winston Smith does, so we put our hopes in the majority of the population, but the efforts of the imperial propagandizers are devoted to avoiding the threat of overthrow of the elites currently in power in each of the three empires.

We have always been an empire.