While Montaigne initiated the literary form of the personal essay, and did it so well that millions of writers since then have followed his lead, I confess that I’m no Montaigne.

I find inspiration for setting out my ideas, half-finished as they are, in an essay from one of my older sister’s hand-me-down Spanish literature textbooks. In The Generation of 1898 and after, according to the anthology editors the easiest-to-read selection (and one which I only read the first few pages, the author “Azorín” addressed his reader in the first paragraph:

Reader — I am a minor philosopher; I have a silver box of fine shredded tobacco, a tall silk hat, and a silk umbrella with strong whalebone struts.

He continues, talking about his country house with a fine starlit night sky, and his small library, with works by Cervantes, Gracian, Montaigne, Loepardi, Vives, and Taine. My own cottage has a view of the large Fred Meyer parking lot across the street, and my cloth caps and umbrellas cannot match his for quality, but my books are considerably advanced in scope and depth. The New Testament in the original, Dostoevsky and his contemporaries in Russian, the first four writers he just mentioned, and at least four shelves full of mathematical physics of the last half of the twentieth century.

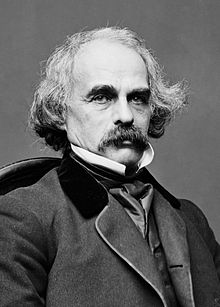

So I am a minor philosopher as well; I just have a very modest ability to express myself gracefully. I am, as Nathaniel Hawthorne, the most famous writer from my birth town of Salem, Massachusetts once styled himself, “the obscurest man of letters in America.”

I picked up, dear reader, the December 2018 issue of the Journal of Modern History this afternoon, and found a review near the back of a book recounting the founding of the Weimar Republic, almost exactly 100 years ago this winter of 2018/2019. The reviewer, a fellow at Cambridge, praises [vol. 90, pp. 976-977] the historian Mark Jones’s balanced presentation of the mixture of resentment by military officials at the defeat Germany suffered during the World War, the reluctance of the civilian revolutionaries who had accomplished the overthrow of the Hohenzollern dynasty of Imperial Germany to establish firm civilian control, and the panic that threw the two groups together to crush, and crush brutally, the left-wing socialists who demanded a worker-controlled, democratic regime.

So where did it all go wrong for Weimar?

That is, a book about the founding of the first democratic regime of a unified Germany has to address the problem of the very weak elite support for a government which relied upon the support of an undemocratic military, which had rejected and suppressed the demands of extremists of their own party, and which to a large extent as a consequence fell victim to fascist action in 1933, only fourteen years later.

Jones strikes a balance in addressing this morally and politically (still!) fraught question. He is unequivocally critical of Noske et al.

That is, he condemns the capture and assassination of left-wing socialists who demanded the resignation of the socialist government of which Gustav Noske was Defense Minister.

The upshot of his study of the rumors and rhetoric of fear surrounding “Russian conditions” is how unfounded and fantastical, how disconnected from reality this central motivation impelling moderates to compromise with the Freikorps Right truly was.

That is, faced with the rumors of a Russian-supported revolution, the socialist government called upon the support of right-wing soldiers’ groups which had little in common with them, politically.

Yet he is also at pains to stress how prevalent and real such fears were — and how instrumental Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg were in promoting the myth of the Soviet reach in Germany (in retrospect both pernicious and fanciful). [Jones] also shows just how incendiary Luxemburg’s rhetoric became after the Spartacus uprising, which she had initially opposed . . .

That carefully-selected library, dear reader, in which your minor philosopher wanders as he savors the ideas of the past includes a volume of the works of Rosa Luxemburg, leader of the left wing of the German Socialist party and founder of the Communist Party of Germany. The most striking thing about her account of the Russian Revolution of 1905, which she wrote in the summer of 1906 for delivery to the German Social Democratic Party Congress at Mannheim, it is that she believed that the workers’ revolution had already begun to overthrow capitalism. If she is now famous for her criticism of V.I. Lenin, if she, as the historian of the Weimar revolution indicates, opposed the uprising that led to her assassination, her soaring praise of the revolution is superb; her optimism conquers her doubts.

Any history of the unsuccessful Spartacus Uprising of January 1919 has resonance today, in January 2019, to a great extent because of the belief by large numbers of anti-fascist agitators, in my city of Portland, Oregon, as well as many others across this country, that we are now in a political situation analogous to that of the Weimar Republic, and that action against overt and covert Nazi activists is necessary and proper.

What close analysis (according to a review of an extended treatment which gained praise from specialists) reveals is, that exaggerated reports of Russian influence precipitated a brutal reaction, a reaction which continued, for more than a decade, and produced exactly that result against which our “antifa” groups of today wish to avert. I see from my four-room cottage in Sullivan’s Gulch (no kidding: that is the name of my neighborhood) one more reason to decline to march in solidarity with the delusionary, violence-promoting extremists of the hour.